Recently, there has been a lot of talk about the “decline of the literary (straight) (white) male.” The marginal benefit provided by an additional take on this topic, some clever new angle walking the tightrope between edgy and politically correct, is rapidly approaching zero.

The problem with these articles—and the discourse as a whole—is that none of them go far enough. There is an impassable chasm between the stardom of Mailer, Updike, McCarthy, DFW, Franzen, etc and whoever is getting fellowships and is published in The New Yorker or Paris Review today. Yet the chief complaint from advocates for the literary men is that they are unfairly denied these fellowships and publications. I’m sure they’re being discriminated against, but you’re just replacing one group of people you’ve never heard of, with a different group of people you’ve never heard of with different sex organs.

This may well be a Title VII problem, but there’s a bait-and-switch happening: the rhetorical appeal of the conversation about literary men depends on the fall-off from The Greats—the juxtaposition between their success and the barren opportunities for literary men today. Yet no one seems willing to contend with the fact that this is not just an issue for literary men, it’s an issue for everyone. What non-identity quality do The Greats have in common that virtually all young contemporary literary fiction writers (Rooney aside), don’t? It’s obvious—people knew about them and bought their books.1

The 21st century collapse in American literary fiction’s cultural impact, measured by commercial sales and the capacity to produce well-known great writers, stems less from identity politics or smartphones than from a combined supply shock (the shrinking magazine or academia pipeline) and demand shock (the move away from writing books that appeal to normal readers in order to seek prestige inside the world of lit-fiction)

To start, take a look at Publisher Weekly’s “list of best-selling novels of 1962:”

Ship of Fools by Katherine Anne Porter

Dearly Beloved by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

A Shade of Difference by Allen Drury

Youngblood Hawke by Herman Wouk

Franny and Zooey by J. D. Salinger

Here’s 1963:

The Shoes of the Fisherman by Morris West

The Group by Mary McCarthy

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, and Seymour-An Introduction by J. D. Salinger

Caravans by James A. Michener

Elizabeth Appleton by John O'Hara

It feels a little cruel to rub it in, but for comparison’s sake here’s 2023:

It Ends with Us by Colleen Hoover

It Starts with Us by Colleen Hoover

Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

Atomic Habits by James Clear2

Dog Man: Twenty Thousand Fleas Under the Sea by Dav Pilkey

Some miscellaneous facts:

Portnoy’s Complaint was the best-selling book of 1969

James Jones’s From Here to Eternity (861 pages) was the best-selling book of 1951

Lolita made it to #3 in 1958 and held on at #8 in 1959 (the #1 spot in 1958 belonged to Doctor Zhivago)

Ragtime was the best-selling book of 1974

The Corrections — #5 in 2001 — was the most recent work of literary fiction to make the yearly top ten best-sellers

No work of literary fiction has been on Publisher’s Weekly’s yearly top ten best-selling list since 2001

Percival Everett’s James is the most recent work of literary fiction to make the New York Times’s weekly bestseller list — it was the best-selling book in the last week of 2024

Before James, the most recent one was Amor Towles’s The Lincoln Highway for one week in October 2021

In the mad rush for stability among a shrinking pool of resources (financial and cultural), authors and discourse-makers seem to have fallen into malaise bickering about how these resources should be divided up instead of why the pool is shrinking at all. It doesn’t matter that no white man born after 1984 has been published by The New Yorker, because I honestly doubt any serious reader of fiction could easily bring to mind a short story by any younger writer in The New Yorker at all. The gap between now and The Greats matters for all writers, not just men. So the real problem is literary fiction’s wholesale decline, not how the ever-smaller pie gets sliced up.

After reading some articles on the decline of American literary fiction, I came away with the sense that no one is particularly interested in why literary fiction’s relevance has plummeted, instead the authors of these pieces are intent on proving only whether or not salient issues like smartphones, discrimination, or woke publishers might have something to do with it. But while it’s not difficult to cobble together a story about why these issues might have had some effect, no one has bothered to ask whether these are really the drivers—if they drive the discourse, surely they’re the actual causes right?

Let’s look at two representative articles that touch on the general decline of literary fiction: Will Blythe’s The Life, Death—And Afterlife—of Literary Fiction from 2023 and ARX-Han’s more recent The decline of literary fiction and the principal-agent problem in modern publishing.

Han has a compelling thesis that fits in alongside the recent complaints about anti-male discrimination in publishing:

“Here’s one hypothesis behind the decline in modern literary fiction: I believe that the literary market has become less efficient because of an increased degree of principal-agent conflict between editors and their publishing houses.

I suspect that the reason for this increased principal-agent conflict is increased status competition between literary editors driven by the culture war. To me, it seems like editors are competing on the axis of moral status.

The overriding imperative behind “elevating diverse voices” in publishing is actually an axis of moral competition between literary editors.”

It’s quite clever: editors are competing on status and correctly (from their perspective) optimize for diversity instead of quality. This is an interesting theory, but it’s not a great explanation for the general decline in literary fiction’s quality, sales, and cultural capital for a fairly obvious reason—the timing doesn’t work.

From Alex Perez’s FP piece that Han references:

It began, really, in 2010, 2012,” the award-winning author Lionel Shriver, best known for her novel We Need to Talk About Kevin, told The Free Press.”

This is simply too late in time to satisfactorily explain the decline of literary fiction; maybe it can speak to some of the quality and popularity decline post-2010, but a full explanation should be able to explain a steady decline in consumer popularity beginning in the 1980s & 90s until almost complete collapse in the early 2000s. Nothing about Han’s theory can explain, for example, why no work of literary fiction has been a yearly best-seller since 2001.

I’m also not fully convinced by the structure he sets up. I agree that there is a divergence between sales and editor status optimization, but I’m not sure why the mode of optimization should be moral status. Another mode of optimization that is orthogonal to monetary success is critical acclaim — if the book you edited or published won a Pulitzer/Booker it feels intuitively that you’ve out-statused some other publisher’s accrued diversity/identity status. Of course it’s much easier to accrue status by way of the ‘moral status’ Han talks about, but this cuts both ways because this sort of status that is easy to acquire won’t be worth as much as ‘connection to literary prestige’ which is much harder to get. And there is of course another related principal-agent problem at work here with authors themselves—literary fiction probably being unique among subgenres in that it feels like authors value awards and the opinions of critics far more than sales. More on that later.

No one can deny that publishing has ‘gone woke,’ but this alone is insufficient to explain literary fiction’s nosedive.

In the 2023 Esquire article, The Life, Death—And Afterlife—of Literary Fiction, Will Blythe offers up another explanation:

“In the past twenty-five or so years, the magazine industry has shrunk in the midst of this “dataism,” particularly in its rendition of literary fiction. Three years ago, Adrienne LaFrance, executive editor of The Atlantic, decided to help devise an online destination for such fiction, short stories in particular, beginning with one by Lauren Groff. “The thinning of print magazines this century,” she writes, “meant a culling of fiction.” The internet, in her estimation (and mine), “makes fairly efficient work of splintering attention and devouring time.” As a result, she concludes that literary reading is “far too easily set aside.”

Why did magazines go under, why does no one read literary fiction anymore? “The internet,” Blythe sternly replies.

People don’t read books or short stories in magazines anymore because they’re too busy scrolling? There’s data on this: according to the National Endowment of the Arts, the number of Americans who “read literature” has fallen from 56.9% in 1982 to 46.7% in 2002 to 38% in 2022. I’m not even going to bother pulling data on the percent of time people spend on their phones or on the internet. So the internet means people spend less time reading books and (presumably) less time reading literary fiction in particular because it’s weighty, boring, dense, etc. There are two problems with this theory: one is that the facts are wrong — the actual size of the fiction reading population has not shrunk a meaningful amount (population growth), and the second is that even if the facts were right, it couldn’t be correct: in 1955, the number of Americans who even read one book a year (39%) was lower than it is today (53%).3 And the 1950s and 1960s were supposedly the golden-age of American fiction. What’s actually going on?4

It’s obvious that the “distraction” angle is untenable. It hasn’t directly impacted the number of readers enough to matter. Still there are other angles here, what about taste? Blythe’s piece can also be read as saying that phones, the internet, short-form content, etc have changed the way people consume books such that literary fiction is out and poorly written genre-fiction and steamy romance are in.

On face, this is a far more compelling theory: the fiction market is dominated by genre fiction, romance, and James Patterson. Literary fiction makes up something like 2% of the market. People are still reading books, they’re just reading worse books. Why? Ensloppification or something. We’ve explained the fall of literary fiction and it’s still the computer’s fault.

But there is some data that fits very strangely into this picture. For one, people still read plenty of literary fiction, what they don’t read is contemporary literary fiction. Books like Pride and Prejudice, War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, etc still sell many thousands of copies every year, more than even big hits in contemporary literary fiction.5 And look at any survey of contemporary audiences' favorite books. Plenty of literary fiction there.6 So I think there’s a strong enough warrant here that the ‘taste-change’ hypothesis can’t be right either — unless the internet made people’s tastes magically shift away from contemporary literary fiction but not classics.

To understand what’s happened to literary fiction, then, perhaps it’s worth trying to disentangle two tightly linked problems: the commercial failure of literary fiction and the critical failure — the lack of a young Great writer. By now it’s obvious that the former problem exists, but you might be skeptical of the latter.

It’s hard to talk about “masterpieces” because the concept trades on a theory of aesthetics that is controversial when spelled out (aesthetic value realism; maybe even a kind of Platonism about beauty) and difficult to defend, but which we all nevertheless subscribe to intuitively.

Some books widely praised as classics and masterpieces in their time are forgotten soon after. Many books that a lot of people like are simply not any good. But far rarer than these cases are books that are forgotten in their time and “discovered” as masterpieces. For the last twenty years American literary culture has been unable to produce a writer we can describe as great without at least feeling a tinge of embarrassment about. We should be worried.

I first got the sense that something had gone wrong when, in high-school English class, we read One Hundred Years of Solitude followed by Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award winning Salvage the Bones. It’s not that Salvage the Bones was not a serviceable book: well-plotted, believable characters, etc, but it was impossible to not deny that these two books could even be put on the same level.7

“What about x, y, z? They’re really pushing the boundaries of fiction as a medium.” I don’t want to be mean, but I doubt it. At this moment, there are not even any famous literary fiction writers (much less geniuses) in the United States of America under the age of 65. If we can argue about it, you’re wrong. This was not the case in 2000, 1990, 1980, 1970, 1960, etc. Before we even get to the problem of sales, we need to know what’s gone wrong with the talent pipeline.

The Supply Side

Blythe is right about one thing—the internet killed magazines, not because people’s brains turned to mush, but because of the loss of advertisement revenue. U.S. consumer-magazine ad spend almost halved from 2004 to 2024 as brands chased cheaper, better-targeted impressions on Google and Facebook. It was those magazines that didn’t rely primarily on advertising revenue which survived and are thriving today. The New Yorker, for example, is still profitable and currently has a paid circulation of 1.3 million, more than double what it had in the heydays of the 1950s and 1960s.

Still, the magazines that survived could no longer afford to give as much space to short stories or compensate their writers well — as crazy as it sounds it was possible to make a living writing short stories and publishing them in periodicals both in pulp publications and more prestigious magazines.

The collapse of the magazine ecosystem is important not because it meant less people were reading literary fiction, but because it thinned the talent pipeline — there were less opportunities to get published and less money for you if you did.

But the magazine-side is only part of the picture, the other problem was in academia. From US Doctorates in the 20th Century:

“Earning a doctorate during the first 70 years of the 20th century typically assured the graduate of a position in academe…Humanities Ph.D.s had the highest rate of academic employment—83 percent in 1995–99—but lower than the 94 percent level in 1970–74.”

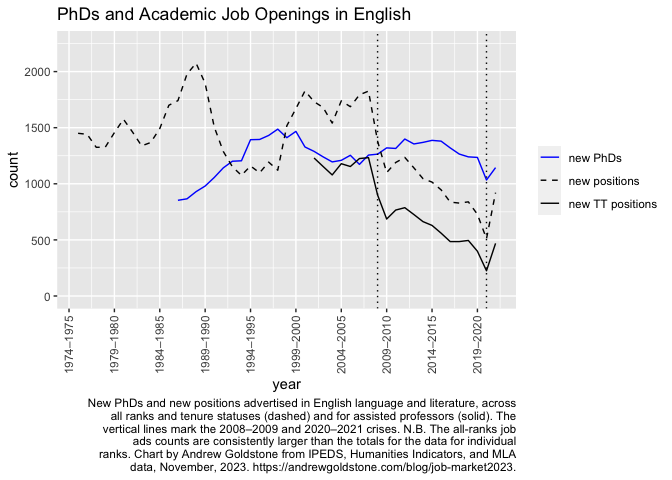

Since a peak in open positions in 1984, the number of new English teaching positions has plummeted while the number of PHDs has held steady.

The same problem holds true for creative writing: in 2016 there were 3,000 MFA graduates and 119 tenure-track positions.

Writers can no longer make a good living writing freelance for magazines, and they’re unlikely to find solace in the academic job market either. Worse — even if they do get credentials and manage to find a publisher, most likely their book will have meager sales of a couple thousand copies. If they want to write and make a decent amount of money, where can they go?

From a financial perspective then, one attractor away from the pipeline into writing literary fiction comes from the rise of prestige-television over the last several decades. The showrunners of Mad Men, Game of Thrones, and True Detective all have creative-writing MFAs.8 Before the advent of prestige TV and the decline of magazines and academia, there was little risk that writers of literary fiction would turn from writing novels to the screen.9

The talent pipeline for literary fiction has shrunk considerably over the past several decades. Anyone with a shred of care for financial success has essentially been filtered out. And even if literary fiction started to sell again this would still largely be true — Writing a book has always been a lottery ticket, even when the market was in a better condition — a small percentage of books drive almost all of the sales.

Imagine the pool of potential writers, people who, if they had the opportunity, would spend their entire lives writing literary fiction and a few of them even having the innate talent and capacity to go on and become “Great” writers after many years at work. The recent loss of two clear pathways to live such a life has shrunk this pool drastically. No wonder then that we haven’t seen any genius fiction writers in quite some time.10

The Demand Side

But this is only half the problem. The public used to gobble up literary fiction, and not just groundbreaking masterpieces: fiction that was just good. John O’Hara was a good writer. No one today remembers his book Elizabeth Appleton, but it was the fifth best-selling book of the year in 1963. No one has ever called Katherine Anne Porter’s Ship of Fools a masterpiece (she herself eventually dismissed it as ‘unwieldy’ and ‘enormous’), but it was the best-selling book of 1962. And so on with many of the lesser novels of the Greats and many middling works of literary fiction by authors that have been forgotten today. But from the 1970s onward, fewer and fewer works made it onto the best-sellers lists. Why is this no longer the case?

It can’t be because book readers have drastically changed their preferences: they still like to read literary fiction (including plenty of non classics/masterpieces — A Prayer for Owen Meany, The Outsiders, A Secret History, Rebecca, etc all sell very well to this day) and only seem to have a problem with contemporary literary fiction.

Something about literary fiction has changed in recent years that has put it off to mass audiences. Han locates the change in “wokeness,” but the timing doesn’t work — this shift was already in full swing before the 2010s when “woke” became a salient issue.

On her excellent blog, Naomi Kanakia notes the following:

Our literary culture has lost faith in ‘the general reader’

Since starting this newsletter, I have become very familiar with…intelligent people who read books and are interested in literature, but are not connected to lit-world discourse.

However, I find that, in practice, it is very difficult to convince the literary world that folks like [this] actually exist. They believe readers exist, but they tend to think most readers are stupid and don’t like to read smart books. They think that readers of smart books are an endangered species, and that a critic’s primary role is to convince the readers of dumb books to read smart books instead.

But, recently, literary people have started to lose faith even in this rather-condescending goal. Nowadays, literary people have started to conceptualize reading itself as being an endangered activity—they believe that the general public’s actual ability to read has somehow been diminished by the rise of smartphones.

The key here is the following thought: “it is very difficult to convince the reader that [intelligent people who read books and are interested in literature, but are not connected to lit-world discourse] actually exist.”

The principal reason self-conscious contemporary literary fiction sells no books is because it’s all insider-baseball so to speak. There’s nothing in most of these books for the general reader. The books are written for the critics. It’s easy to see how a vicious cycle could have arisen from the preoccupation with status, not sales:

Authors start to optimize for critical praise

Critics feel the need to differentiate themselves, both from other critics and from popular taste so they come up with increasingly baroque criteria to judge these books

Readers are understandably alienated when they pick up new books; total sales drop

The drop in literary fiction sales increases the allure of 1)

And so on in a circle until we’ve arrived at a place where literary fiction is 2% of the fiction market.

How exactly did this cycle start? I think there’s reason to believe it began in the 1970s.11 Here’s one hypothesis:

Consider the case of Philip Roth. Goodbye, Columbus was a best-seller and turned into a movie. Portnoy’s Complaint sold half a million copies and was the best-selling book of 1969. But no Roth novel in the 1970s appeared on any best-sellers list, and considering the brusque experimentation of the novels in question: The Breast, My Life as a Man, and The Ghost-Writer, this is no great surprise. And yet he received critical acclaim during the decade: The Ghost Writer was selected by the Pulitzer Committee in 1980 (though overruled by the board which selected The Executioner’s Song instead) and was a finalist for the National Book Award, The Professor of Desire was nominated for the Critics Circle Award, and all of these books were heavily praised by newspaper and magazine reviewers.

Who else was winning awards at this time? With Gravity’s Rainbow’s National Book Award in 1974 (and refused Pulitzer) it was increasingly postmodern authors like Pynchon, Barth, and Gaddis, none of whom ever sold a meaningful number of books. Their rise signaled the start of a complete decoupling of sales and critical taste. Authors who consciously shunned the ‘middlebrow’ mass audiences of mid-century America were rewarded by the critics. And authors like Roth, who were in ceaseless pursuit of literary status, readily changed their style to accommodate this new environment.

Of course the trends changed and so after postmodernism a kind of MFA minimalism came to dominate literary fiction, a style whose effects are still readily present in any contemporary works one might pick up today. But the broader point is that beginning in the 1970s, authors were willing to optimize for critical praise at the expense of sales to a degree they had not been before.

So from the 1970s onward, literary fiction was seen less and less on the best-sellers list, though the later collapse of the talent pipeline beginning in the 1980s and 1990s with the slowing academic job market and the widespread failure of print magazines, is what finally killed off its commercial prospects.

Conclusion

There are still some important open questions: the exact role of the critics in moving authors away from popular taste, the involvement of publishers, and the saliency of this essay for non-US authors and markets (the case of Sally Rooney is quite interesting). But I will conclude this essay here with some parting words.

I think the most important conclusion is that all of this is actually good news for aspiring writers: it’s not that the philistine dopamine-addled masses will never be capable of giving you the praise you deserve, it’s just that (1) basically no one is writing literary fiction and (2) the present-day norms of literary fiction mean that the general reader will never like anyone who is. Both of these problems are easier to fix than drastically changing the reading tastes of the entire population. But how will they be fixed? I’m not sure.

I don’t think magazines with short stories are ever coming back. The situation in academia will likely not improve. But I do suspect Substack will play a role in broadening norms and making it easier to write literary fiction. I think the advent of the internet, though it killed the magazines, will someday be seen as a godsend for writing. Although on the topic of technology, if LLMs or AI have any part to play in this story, it will likely not be a good one. But knowing that the fate of literature is still in the hands of writers, I’m optimistic.

One of the problems with discussing this topic is that it’s almost impossible to get sales numbers on any recently published book unless you work in publishing and can shell out a couple thousand a year for BookScan and even then you’re not even necessarily getting an accurate measure of the sales. So I’m forced to work with surveys, suspect aggregate data, anecdotes, and various wish-wash to make a case. Probably one of the reasons that people who talk about this never want to get into the numbers.

I’m not sure why they included a self-help book in a list of best-selling novels

Spending on recreational books per-capita (index / population) was also not higher than it is now

Of course one way to answer the question would be to flip our findings around. You could say “the reason all of those great literary books were on the charts was because no one was reading books except people with good taste. The reason Colleen Hoover tops the charts now is precisely because everyone reads.” It’s sufficient to note that while this makes sense across the 1955 and 2022 data where there is a dramatic shift in the number of readers, the number of readers from 1982 onward is similar to the number of readers today. Literary fiction still made it onto charts up until 2001 and there’s no shift in readers that could explain its appearance and disappearance post-1982 since the numbers are the same.

An interesting way to pushback here might be to ask how many of these sales are to schools. Still, I think this is defanged by the sales numbers of classics which are not often taught in school for logistical reasons like War and Peace, along with non-classic works of literary fiction like John Irving’s books which still sell quite well.

You might say that the survey data is just signalling and people claim to like more sophisticated books than they actually do, but I think this, combined with the sales data, is a compelling enough case to suggest that reading tastes have not drastically changed away from literary fiction in general.

I’ll admit I did not enjoy the book, but I’ll resist the urge to go as far as critic D.G. Meyers: “If there were an award for best novel for grammar school readers, Salvage the Bones still would not have deserved it.”

Nic Pizzolatto of True Detective fame is a great example because he was huge in contemporary literary fiction circles before he turned to television. Now he’s writing scripts for Marvel movies.

Of course this sort of thing was not uncommon in the early years of film: Fitzgerald, Chandler, Faulkner, Huxley, etc

This certainly does not hold true for criticism, screenwriting, and other kinds of writing by these once potential literary fiction writers.

Epistemically, this section is the shakiest. Literary fiction peaked on the charts in the 1950s and 1960s and was quite present before then. There was a sustained decline from the 1970s onward. I think the vicious cycle mechanism is definitely correct, and my story about the postmodernists is one way this could have happened, but I haven’t studied this period exhaustively enough; there might have been other factors at play.

I’m tempted to say it’s because they don’t read my novels but self-pity is no substitute for analysis, although it’s often a starting point. My real belief is that the widespread study of literature in academia planted the seeds of its decline in a variety of ways, culturally and in the marketplace.

One number I never tire of quoting is that, according to the British Publishers Association, in 2023 the *median* first-year sell through rate for literary fiction in the UK was just 241 copies.

I’m no insider but I do know a little about the Canadian publishing business. I think it is telling that, a couple of years ago, Ontario dropped the requirement for companies to print at least 500 copies of a book in order to qualify for the provincial tax credit that keeps many small publishers afloat. I take this to mean that book sales in general are so poor that shifting 500 copies is unrealistic for most titles.